Why Torino Fans’ Patience With Urbano Cairo Is Running Out

By Dan Cancian

There was a revealing vignette about the simmering malaise around Torino last week.

On June 19, the Granata’s official X account shared a black and white image of Luca Fusi lifting the Coppa Italia at the Stadio Olimpico 32 years ago.

It was Torino’s fifth Coppa Italia and remains their last piece of silverware, one secured in typically dramatic circumstances after drawing 5-5 on aggregate with Roma to take the trophy on away goals.

Social media is seldom the place for nuanced debate, but the responses to the post were telling of the growing frustration around the club.

They verged from lamenting the lack of success over the past 30 years, to condemning the absence of ambition. Almost unanimously, they laid the blame for both firmly at Urbano Cairo’s feet.

It is an interesting paradox, for the 68-year-old is arguably responsible for one of the most trouble-free periods in Torino’s complicated history.

The Coppa Italia triumph in 1993 came with the club embroiled in investigation for fraudulent bankruptcy, false accounting, and embezzlement.

Gian Mauro Borsano, whose loose approach to financial regulations had taken the Granata from Serie B to a UEFA Cup final in the previous three seasons, had sold the club to Roberto Goveani for 12bn lire (£5.2m at the current exchange rate).

To put the figure into context, a year earlier Torino had sold Gianluigi Lentini to AC Milan for five times the price.

Goveani and Borsano were both eventually arrested – the former in 1994, the latter in 2001 – amid a plethora of charges ranging from embezzlement to illicit payments and fraud, while the Granata passed from dubious owner to dubious owner.

Three years after the Coppa Italia triumph Torino dropped down to Serie B, the first of three relegations over the next seven years, which culminated in bankruptcy in the summer of 2004.

A year later, Cairo – one of Italy’s biggest media moguls – arrived on the scene.

Torino returned to Serie A and, bar a three-year spell in Serie B from 2009 to 2012, have been a fixture of calcio’s upper echelon ever since.

That is the their longest run in Serie A since 1989, when they were relegated to the second tier for only the second time in their history.

Under Cairo, the Granata have finished in the top half of Serie A in eight of the past 13 seasons and played European football in 2015, when they also won the Derby della Mole for the first time in 20 years, and 2020.

But in the eyes of the fans, he has long stopped playing the role of the benefactor. That is if he ever took on the part at all.

Protests against the ownership were near-ubiquitous at the Stadio Olimpico last season. Cairo’s popularity is at such a low ebb that “Cairo, f*** off and leave” graffiti was scrawled on the road during some of the Giro d’Italia Alpine stages. It is a particularly stinging message given he is the CEO of RCS MediaGroup, which controls La Gazzetta dello Sport, the Giro’s organiser.

Cairo has steadfastly refused claims he lacks ambition, pointing to his investment.

Since returning to Serie A in 2012, Torino have spent over €20m (£17m) on players just five times, all of which have come in the past six seasons.

Perhaps more significantly, they have run a negative net spend just five times in the past 13 years.

Cairo can justifiably point out that his relatively thrifty approach to spending has allowed Torino to balance the books and move closer to becoming self-sustainable.

Against Torino’s litany of financial issues in the two decades before his arrival, that is no mean feat. But the problem with that approach is that it becomes difficult to justify when it does not deliver results. The focus on making the club self-sustainable is admirable, but at what cost? The line between being a permanent fixture in Serie A and mediocrity is a fine one.

Torino have not challenged for a trophy in 32 years. Over the same period, Napoli have won the Scudetto twice and the Coppa Italia three times.

Sampdoria, Fiorentina, Vicenza, Parma and Bologna have lifted silverware too.

Atalanta have gone from Serie A also-rans to Champions League regulars and won the Europa League in 2024.

Success, in short, is not restricted to the usual corridors of power in Serie A.

On the flip side, the balance-sheet Scudetto these days is as important as trophies.

Just ask Milan, who did not break the €30m barrier on signings in three years after RedBird took over from Elliott Management until January.

Marco Baroni is the man tasked with taking Torino forward next season, the former Lazio manager replacing Paolo Vanoli after a solitary term in charge.

“Our aim is to improve and take a step forward,” Cairo said last week. “To do so, we’re focused on strengthening the squad. We have clear ideas on what needs to be done and how to do it.”

There are reasons to be mildly optimistic. Baroni had Lazio challenging for a Champions League spot until the final day of the season and Torino won the Under-18 Scudetto earlier this month, with their U17 colleagues following suit a week later.

But if the future looks bright, the present remains underwhelming at best. As the responses to Torino’s post on X pointed out last week, a generation of Granata has never seen their team compete for a trophy, let alone win one.

Until that changes, each anniversary of the Coppa Italia triumph will be a sombre event.

Related Articles

Related Articles

We get a local take on what's hot in Cremona - where to eat and drink, sights to see and handy hints that might not be in the tourist guides.

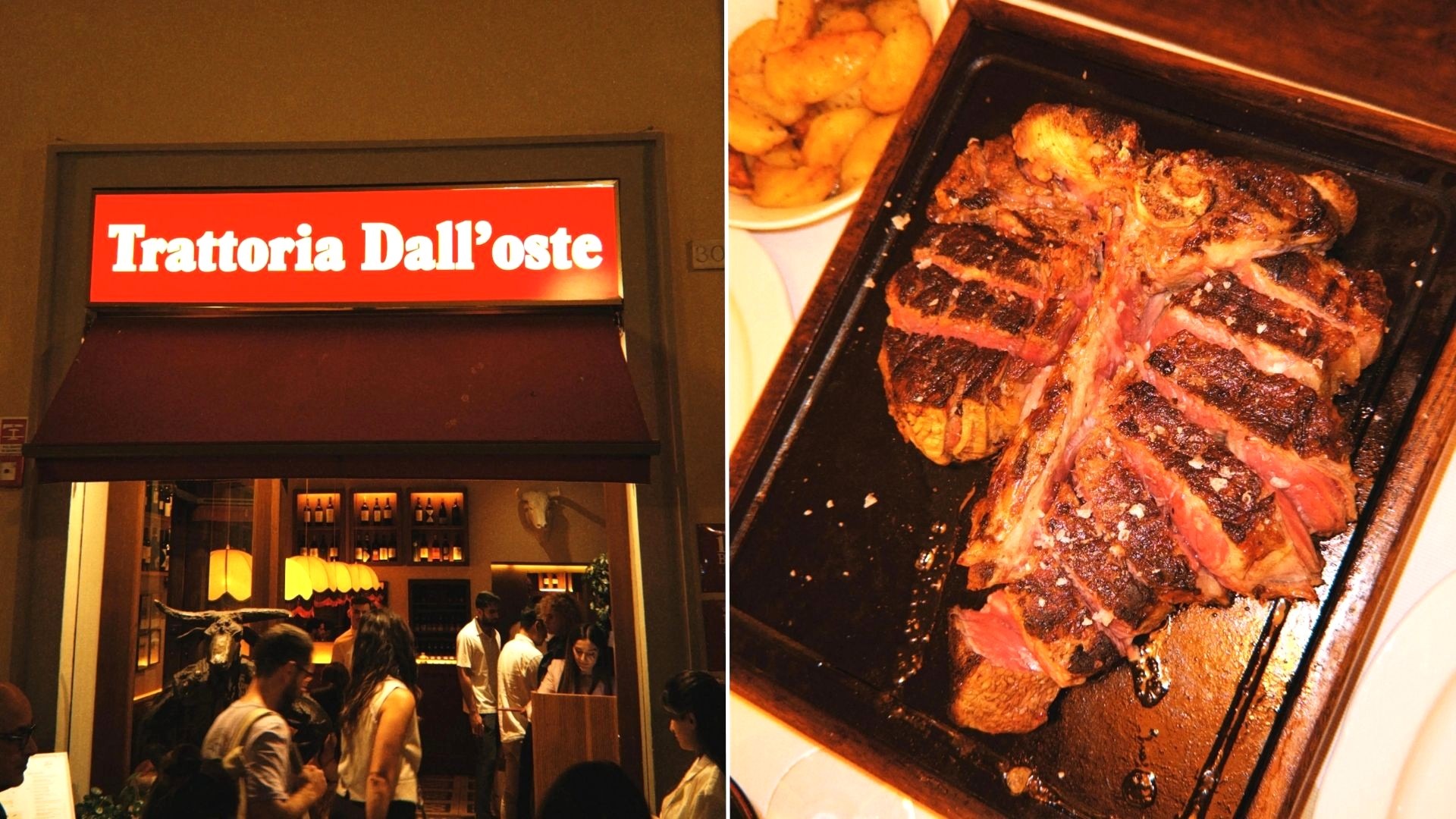

The Artemio Franchi will always be the main reason calcio fans head to Florence but there is one other thing that must be on the to-do list.

After the final whistle is blown at Stadio Giuseppe Sinigaglia, there is no better place to unwind than Bellagio.