The Day Verona Ruined Diego Maradona’s Napoli debut

By Emmet Gates

Naples, and by extension Serie A, had never seen anything like it. July 5th 1984 — 40 years ago this summer — saw the world’s best player arrive on Italian shores. Diego Maradona swapped Catalonia for Campania in a deal scarcely anyone could believe happened.

As well documented, Maradona wanted out of Barcelona after two nightmarish years but, with his reputation not exactly sparkling amid rumours of partying and the occasional dalliance (at this stage) with white powder, there wasn’t exactly a queue of clubs lining up to take him.

By his own admission, Maradona knew little of Napoli and of Italy: “Napoli meant no more than something Italian, like pizza,” he wrote in his 2000 autobiography El Diego.

It sounds almost fictional, considering the talent in question, but Maradona had to join Napoli, who’d won nothing but a couple of Coppa italia titles in their history, out of necessity: “I was left with no money [after Barcelona], but there wasn’t another team that would buy me,” he later admitted. Yet in hindsight it was the perfect match: he needed them as much as Napoli needed him.

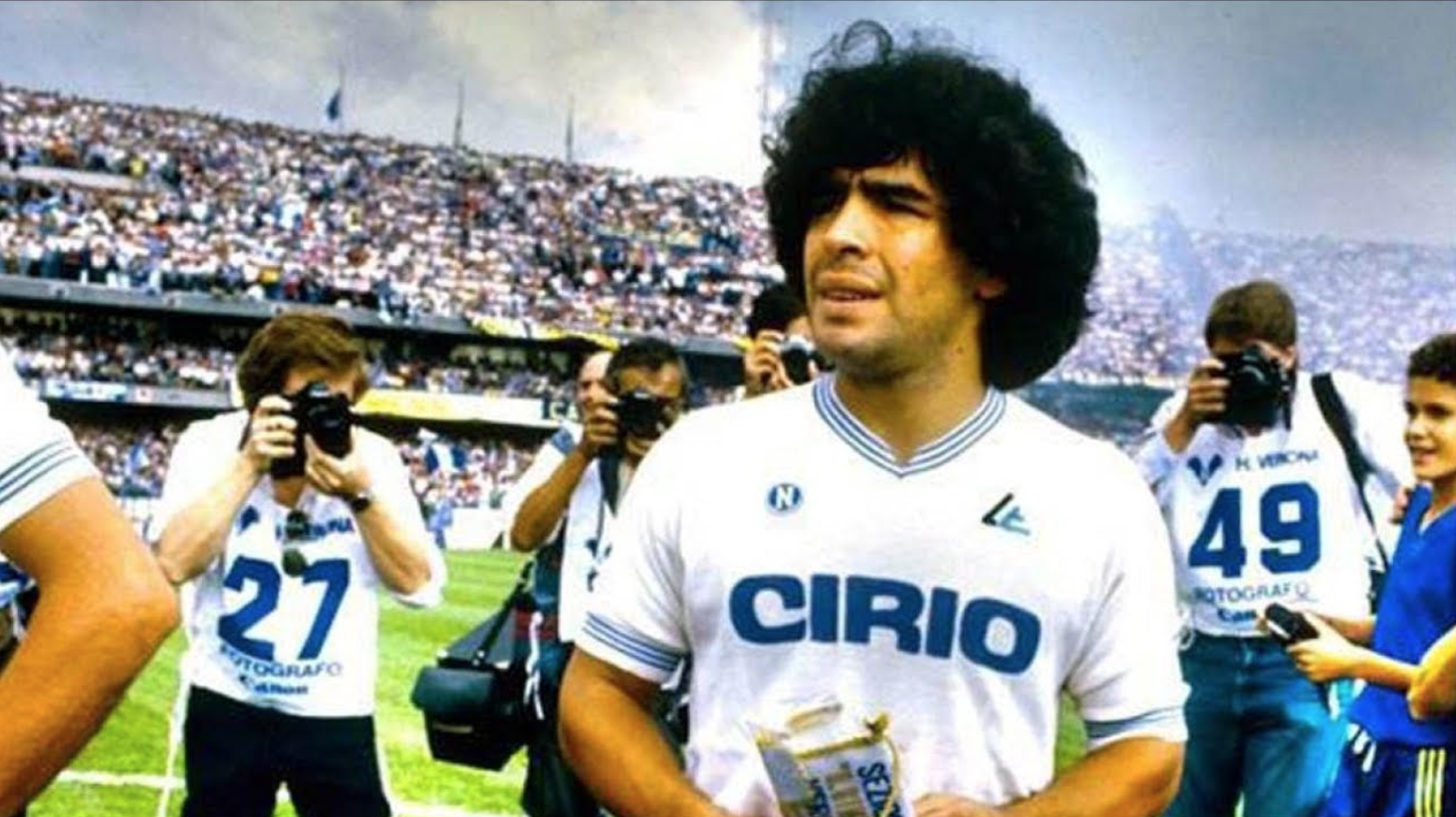

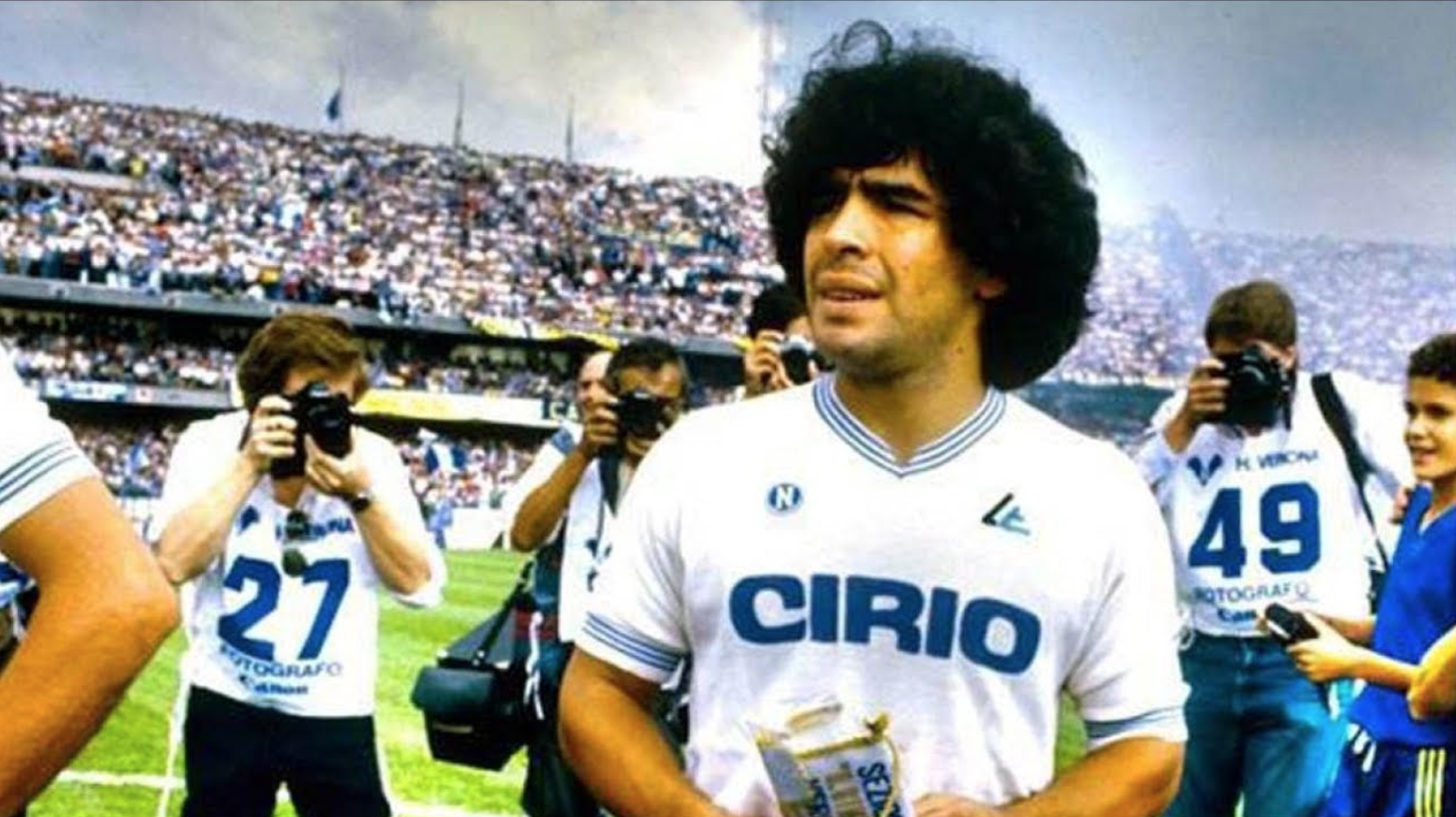

The day of Maradona’s unveiling, perfectly captured at the beginning of Asif Kapadia’s absorbing 2019 documentary on Maradona, shows the chaos and euphoria that would come to epitomise his seven years in Naples. The buzzing of cars can be heard all around, including the car Maradona is in as it roars towards the outer concourse of the cavernous Stadio San Paolo. It’s manic, raw, electric.

The image of Maradona walking up the steps that lead out to the pitch of the San Paolo, complete with a sea of photographers waiting to snap, remains one of the most iconic football images in Italian football history that doesn’t contain any actual football.It’s just a lone 23-year-old glancing over his shoulder to his left, about to enter the anarchy that was to be the next seven years of his life. Trying to avoid being crushed by the weight of the exptectation of an entire city.

Some 80,000 people crammed into the San Paolo to see the Argentine unveiled. Standing in the centre circle of the pitch, Maradona was handed a microphone and said nothing more than: “Good evening, Neapolitans.” In reality, he didn’t need to say anything else, he would do his talking on the pitch. He performed a couple of solos before kicking the ball high into the Napoli sky, sending the fans home happy. Serie A has never seen that many people inside a stadium for a signing, before or since, and in many ways encapsulated Maradona’s life: one of extremes and no half-measures.

After a lap around the stadium blowing kisses, the Napoli fans were already in love with their new hero. Looking back, it’s quite odd to see flares being let off at a stadium for an event that amounted to a 15-minute presentation, but this was Naples and this was Maradona. The team Maradona just joined wasn’t exactly dotted with brilliance. In fact, Napoli had just finished 11th in a 16-team Serie A and were one point above the relegation zone.

The Napoli Maradona joined was a poor outfit that did possess a crop of decent youngsters, in the shape of Ciro Ferrara and Ciccio Baiano among the ranks, in addition to stalwarts such as defender Guiseppe Bruscolotti and goalkeeper Luciano Castellini.

Napoli were, by Maradona’s standards, a ‘Serie B team’.

In addition to Maradona, Napoli president Corrado Ferlaino also signed Daniel Bertoni from Fiorentina and Salvatore Bagni from Inter, adding some class. Yet it was fairly evident that at a time when Serie A was brimming with world-class talent and arguably the most competitive division the game of football has ever seen, this Napoli side wasn’t going to win trophies right away.

That same summer saw Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, Socrates and Graeme Souness join the galaxy of stars already in the league, such as Zico, Falcao, Michel Platini and Liam Brady.

Yet because Napoli had the world’s best player, expectations were through the roof regardless. The kid from the shanty town just outside Buenos Aires was going to lead Napoli to glory, went the Neapolitan rhetoric. He would, but not yet, not with this team.

Maradona’s nightmare debut

Maradona’s first game in Italian football was away to Hellas Verona on September 16, and for the first time caught a glimpse of the territorial racism that’s existed in Serie A for decades or, to be more frank, the perception of Napoli by northerners

Running out on the pitch at Stadio Marcantonio Bentegodi, Maradona and his new teammates were greeted with banners of ‘Lavatevi (wash yourself)’ and ‘Welcome to Italy’. For Neapolitans this was nothing new, but for Maradona it was an eye-opener. “We went up north and, wherever we went, they put up banners that said: ‘Wash yourselves.’ It was disgusting,” he said. “They were all racists.”

Decked out in their all-white away strip, Maradona was of course handed the number 10 shirt that he was to make his own. Going through one of those periods where he grew his hair out, Maradona’s mane was wild and bushy, yet he looked resplendent in the Veneto sunshine, despite 41,000 fans whistling in his direction.

Maradona found his debut tough going. As he would later admit, the tempo of the Italian game was very different to what he faced before in La Liga and in Argentina. “Italian football was played at a different rhythm, and the football was rougher” he told Kapadia. “I had to adapt and learn to play at a different speed.”

Against Verona, Maradona attempted to play as he always had done, running at players and using his speed and agility to skip through the lines, yet it didn’t succeed as he was often double or triple marked by Verona opponents much larger than him.

Maradona would find all this out in time but, considering it was his debut, relying on his natural instincts was understandable. “I had to find a balance, and that wasn’t easy,” Maradona would later reflect on changing his style.”It’s clear that for Diego, no muscle mattered more than the brain,” articulated journalist Gonzalo Bonadeo. Maradona adapted fast and would soon be leaving players in his wake, becoming almost unstoppable in Serie A.

Verona took the lead through a towering header from German midfielder Hans-Peter Briegel, also making his Serie A debut. Briegel would go on to play a pivotal role in Verona’s Scudetto win, arguably the greatest feat in Serie A history.

Verona’s new signings steal the show

And in this game he clung to Maradona, leaving him little room to work any magic. Briegel’s header arrived within the opening 25 minutes of the game, and a little over 10 minutes later Verona doubled their lead through some comical defending, as Napoli goalkeeper Castellini fumbled Antonio Di Gennaro’s shot, allowing Giuseppe Calderisi to poke the ball home from three yards out.

Maradona got a taste of just how rough Serie A can be when he received a kick in the chest from Briegel in the second half, which resulted in nothing more than a telling-off from referee Maurizio Mattei.

With just over half an hour left of the game, Napoli found something of a lifeline, when Bertoni ran on to Bagni’s angled pass over the top of the defence. Bertoni, running away from goal, still had a lot of work to do as he controlled the ball with his right, before smashing a volley with his left, the ball nestling into the bottom corner of Claudio Garella’s goal. It was a marvellous — if ultimately fruitless — goal.

Maradona showed flashes of genius, especially in one sequence when running into the centre circle and being chased by Danish striker Preben Elkjaer, Maradona cuts back, slips, gets up and dummies Elkjaer in one, almost fluid motion.

Elkjaer, who would go on to have the season of his life in the 1984-85 campaign, subsequently falls to the ground bamboozled. It was a warning from Maradona to the rest of the league that, in time, he would bamboozle everyone.

Maradona was going deeper and deeper in search of the ball, but Verona killed off any hope of a comeback, as Di Gennaro headed home the third 15 minutes from time from a set piece.

For the Argentine it was a chastening lesson in the rigours of the Italian game, and the player himself was well aware Napoli needed reinforcements if they were to hold any aspirations of winning anything in the coming years. “We built Napoli from the bottom, it was proper workmanship,” Maradona later wrote.

Verona, led by the goals of Briegel, Elkjaer and Galderisi, would win the Scudetto that season by four points ahead of Torino (in the two-points-per-win era). It remains one of the greatest miracles in football history and, given how the game has shifted so much in the 40 years since, it’s likely it will never happen again.

For Maradona and Napoli — who would finish eighth that season — we all know how the story unfolded: Scudetti, cups, addiction, the Camorra, scandal, betrayal, goals and the redemption of a city that was impoverished and mocked for so long. But all that was to come, for on that Sunday in September 1984, Maradona was given a lesson in calcio and saw the challenge that was ahead of him, and that’s how he liked it.

Destination Calcio is committed to Italian Football. Watch our podcast recorded at the Maradona Murales in Naples.

Related Articles

Related Articles

Football rivalries, world-class sport, surreal carnivals, and a tradition you won’t find anywhere else. Five events to catch in February.

In the latest edition of My Town, My Team, Napoli fan Alex told us why everybody should visit Naples at least once.

Sampdoria against Palermo at the Stadio Luigi Ferraris is just one of the standout matches to be shown live on Destination Calcio TV.