Roberto Baggio at USA ’94: The Man Who Died Standing

By Emmet Gates

It’s one of the most brutal images in football history, and it’s not of a player getting cynically scythed down by a callous defender. It’s of two men in a single bit of frame, one is on his knees close to the goal, looking towards the sky; the other is of a man close to the penalty spot, hands on hips, head sunken, his life stopping for a brief moment, knowing it will never be the same again.

The image in question is of course the final of USA ’94 — 30 years ago this summer — in the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. The two players were Brazil’s Claudio Taffarel and Italy’s Roberto Baggio, one in green, the other in blue, both highlighting the fine margins between ecstasy and despair.

Baggio had just spectacularly blazed his penalty over the crossbar and into the California sky, signalling the last action of a tournament he had come to dominate in the latter stages. There was a certain irony in botched penalties bookending the competition, with Diana Ross’ infamously skewing her penalty wide in the opening ceremony a full month prior. Yet most look back now on Ross’ penalty and laugh; the same can’t be said for Baggio’s.

That one picture has come to define not just USA ’94 and America’s attempt to take the beautiful game seriously but — for right or wrong — Baggio’s career. For a man who won the Ballon d’Or, Serie A titles with Juventus and Milan, the UEFA Cup with Juve and produced one of the finest catalogue of goals in the history of the sport, many still think to this moment when Baggio’s name is mentioned.

It’s unjust, and most forget that without Baggio, Italy wouldn’t have come close to the final, let alone to be in a position to lose it.

Group stage struggle

Going into USA ’94, Baggio couldn’t have been in better form: he was the reigning Ballon d’Or and FIFA World Player of the Year holder, had just scored 22 goals for Juventus in all competitions, was by a clear distance the best player on the planet and, at 27, at the peak of his powers.

However with Baggio things were never that simple. His body, ever fragile, was letting him down at the wrong time.

Suffering from tendonitis in his right achilles heel, Baggio looked a million miles away from the player that dominated Serie A in the period between Italia ’90 and USA ’94. Against Ireland in Giant’s Stadium, he was easily marshalled by Paul McGrath in Italy’s opening game, resulting in a 1-0 loss that remained Baggio’s only World Cup defeat in 90 minutes from 16 games.

Things were to get even worse in the second match.

Italy’s defeat to the Irish meant another one against Egil Olsen’s boring-but-disciplined Norway simply couldn’t have been tolerated if they had any aspirations of making it out of the group stage. Norway, then ranked sixth in the FIFA world rankings, weren’t going to be pushovers.

A cagey opening 20 minutes then sprang into life when Norway took advantage of Antonio Benarrivo’s slackness in getting up to speed with Italy’s high line. Goalkeeper Gianluca Pagliuca came racing off his line and blocked Oyvind Leonhardsen’s shot with an outstretched hand.

Now, there’s nothing unusual about that sentence, save for the fact that Pagliuca was yards outside the penalty box when he saved Leonhardsen’s shot, giving German referee Hellmut Krug no other option than to send the Inter Milan goalkeeper off.

Italy were reduced to 10 men and, to the world’s astonishment, Sacchi decided to replace Baggio with second-choice stopper Luca Marchegiani.

A flabbergasted Liam Brady, performing commentating duty for Irish broadcaster RTE and a former Serie A player, summed up Sacchi’s remarkable decision best: “Sacchi is gambling his whole career.” It remains one of the boldest choices ever made by a coach at a major international tournament.

Baggio at first couldn’t believe it, thinking it was a mistake. He motioned to the bench upon seeing his number,” this guy is crazy,” he muttered, yet the words clearly audible to a worldwide audience. Off he trudged, looking mystified by the whole episode.

“Nothing like this has ever happened to me in my life,” he said afterwards. Italy won, just, thanks to a goal from the other Baggio, Dino, in the second half.

Sacchi defended his decision in the post-game scrum that circled after the final whistle, claiming he did it for ‘Baggio’s health’ and that he was counting on the world’s best player for the final game in the group against Mexico.

Sacchi’s potentially cataclysmic call paid off, but Baggio’s form didn’t improve. Against Mexico in Washington, Baggio — barring one or two moments — was once more a passenger, this time staying on the field for the full 90 minutes.

Daniele Massaro’s strike early in the second half was cancelled out by Marcelino Bernal, and the draw meant for the first — and only time — in World Cup history all four sides finished on four points. Italy squeezed through ahead of Norway on the basis of scoring a goal more, and advanced to the round of 16 as the last third-placed side, narrowly edging out Russia.

Baggio needed to do better, and the pressure of being the world’s best player and Italy’s leading man was suffocating. Moreover, Baggio’s fitness was lacking, as a bout with tendonitis wasn’t healing. Visibly off the pace against Mexico, to say the Juve star flattered to deceive at the tournament he was supposed to light up was an understatement.

A Round of 16 renaissance

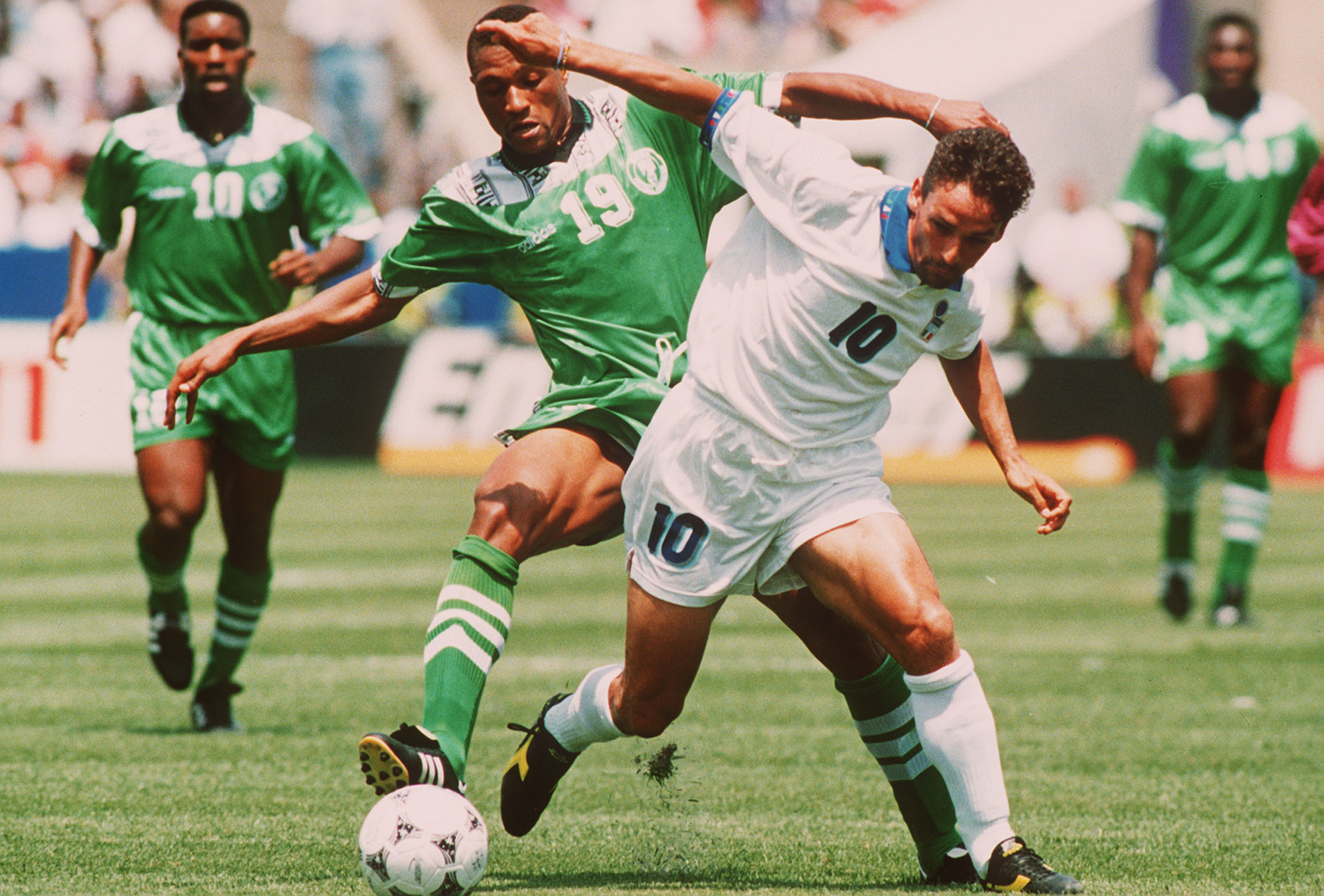

Drawn against Nigeria in the Round of 16, Sacchi persevered with Baggio against the African side, who took a surprise lead through winger Emmanuel Amunike following an accidental assist from Paolo Maldini.

Italy huffed and puffed and the only Baggio who looked remotely threatening was the one sans ponytail, who broke forward from midfield to cause problems in the Nigeria half. Sacchi’s side was struggling against the physicality of Nigeria, and playing in the heat did little to boost their energy.

Gianfranco Zola, who’d been on the pitch all of 10 minutes, was sent off for a supposed rash challenge on Augstine Eguavoen down near the right-hand touchline.

Zola was incredulous, beyond devastated that his World Cup could be over after just a handful of minutes on the pitch (despite Italy making the final, he didn’t play for the rest of the competition and would never feature again in another World Cup). The clock was ticking down, time was running out. And then.

With two minutes left on the clock, right-back Roberto Mussi drifted into the Nigeria penalty box, got a fortunate ricochet and squared the ball back to Baggio, who caressed the ball with his right-foot into the opposite corner of the net.

The strike was slow but precise, nestling into the bottom corner of Peter Rufai’s goal. Finally his duck had been broken, or as Baggio later termed it, ‘getting the house off my back’. It was Baggio’s first goal for the Azzurri in nearly a year.

From then on, it was a different World Cup, and what we saw was one of the few times a single player has taken the tournament by the scruff and driven a team to a final almost single handedly. What Baggio achieved from then-on hadn’t been seen since Diego Maradona in Mexico eight years earlier, and hasn’t been done since.

Baggio netted a second against Nigeria, after a somewhat fortuitous penalty was given after Benarrivo was hauled down by Eguavoen. The decision can only be described as soft, and perhaps there was a bit of karma involved considering Zola’s harsh sending-off, yet up Baggio stepped and scored, just, with the penalty kissing the inside of the post. But it didn’t matter, Italy were through to the quarter final and the real Baggio had finally shown up. “We were on the runway at the airport, ready to go home,” quipped a humorous Baggio after the game. “But I told everyone to get off.”

Spain came next in the quarter final, a game best remembered for two things: Baggio again scoring in the 88th minute — this time the winner — and Mauro Tassotti’s brutal elbow on Luis Enrique that broke his nose, bloodied his white shirt and signalled the end of his international career.

Spain had never beaten Italy at a major international tournament, and their inferiority complex would continue long after USA ’94. This iteration of La Roja wasn’t a particularly good one despite the odd sprinkling of talent, and Italy were still expected to advance to the final four. Things were going as planned after Dino Baggio rifled in one of the goals of the tournament: a scorcher of a shot from 25 yards out that dipped and swerved, giving Spanish goalkeeper Andoni Zubizarreta no chance.

Luis Caminero equalised in the second half, and the game seemed to be going towards extra time, until Nicola Berti seized control of the ball in midfield and saw Beppe Signori breaking through the Spanish lines.

Berti’s floated pass over the top was met by Signori, who shifted the bouncing ball to Baggio before being clattered by a Spanish defender.

It was now just Baggio and Zubizarreta in a duel of calm and verve. Baggio shimmied to the right, leaving Zubizarreta sprawling on the turf, yet his touch had taken him away from the goal and, with the angle becoming more acute, it was going to take laser precision to score.

Baggio didn’t disappoint, angling the ball into the opposite corner of the now-empty goal. It was another clutch moment from the Divine Ponytail, Italy’s plane home was kept on standby and of the five goals he scored in the tournament, this was arguably the most difficult, considering the angle and minutes left on the clock.

Bulgaria’s shocking win against reigning holders Germany meant a semi final showdown between Baggio and Hristo Stoichkov.

Sacchi’s five-year stint as Italy coach can, in retrospect, be deemed a failure: his style of football simply unfit for the sparseness of international football and the lack of time with players, but the opening 25 minutes against Bulgaria demonstrated what could’ve been achieved had Italy been a club side.

The passing was slick, the pressing was high, this was as good as it got under Sacchi.

Baggio scored twice in five minutes.

His first was a magnificent solo effort where, coming off the left-hand channel, Baggio ghosts past Bulgarian defender Peter Hubchev on the periphery of the box before curling a shot into the bottom corner of Borislav Mihaylov’s goal. “Look at that, just look at that,” shouted BBC commentator John Motson. Four minutes later he made it two.

The under-appreciated Demetrio Albertini had nearly scored twice in the moments after Baggio’s goal: one an outside-of-the-boot curler — teed up by Baggio — that struck the post, and the other a delicate chip that nearly caught Mihaylov off guard, only for the Bulgarian to produce a one-handed save, pushing the ball over the bar.

Italy weren’t going to be denied a third time, however. The same two linked up again, with Albertini lofting a pass in behind the Bulgarian defence to the onrushing Baggio, who volleyed the ball from right to left, sending it again into the opposite corner of the net. All five of his goals were put into a corner, a player who was all about killing a goalkeeper softly and never by blunt force.

Stoichkov dispatched a penalty just before half-time to make things a little nervy for Italy. A scintillating first-half gave way to a meandering second. Then came the moment that changed Baggio’s competition.

Making a diagonal run inside the Bulgaria penalty box to meet Roberto Donadoni’s smart pass, Baggio is closed down by Tsanko Tsvetanov. He attempts to wriggle free of the left-back, but mid-twist feels a sharp pain in the back of his right hamstring. Baggio can be seen instantly holding the back of his leg, and the next several minutes of the game pass by before he’s taken off for Signori.

Baggio looked pensive on the bench as the final whistle blew in East Rutherford. Italy had made another World Cup final, primarily thanks to him, but there were serious question marks whether the world’s best player would play in football’s greatest event, with only four days separating the semi finals and final in Pasadena.

“It definitely needs 48 hours of rest, and then we’ll pretty much wait until the last minute,” said Italy team doctor Andrea Ferretti. Never had so much attention been given to the state of a precarious hamstring.

The final nightmare

Travel plans also scuppered any chance of Baggio receiving optimum recovery. All of Italy’s games took place on the East Coast of the States and, with the final in California, travel time would need to be incorporated into the four-day window between games. For a body as fragile as Baggio’s, this wasn’t ideal.

In the end, Italy’s talisman started. Sacchi partnered him alongside Massaro in attack. Yet Baggio’s preparation for the biggest game of his life amounted to training in the hotel, kicking a ball against a wall in a room that hosted weddings. Hardly ideal.

“I would’ve played even if they’d cut off my leg,” he later wrote in his 2001 autobiography Una porta nel cielo [A door in the sky]. By his own admission the injury wasn’t that serious, but was given a painkilling injection to push through what was going to be a slog of a game.

One of the greatest moments of USA ’94 isn’t of a piece of magic, a wonder goal or the vivid colour the American public brought to the games, but in the tunnel just before the final. Italy and Brazil line up, and the cameraman focuses the lens and sees Baggio looking towards Romario, who’d done just as much for the Selecao in getting them to the final as Baggio had for Italy.

Baggio, respectfully, sizes up Brazil’s number 11, who’s oblivious to his gaze. It was a beautiful little moment that catches the tranquility before the storm or, in this case, the insufferable heat of California. Commenting on the clip years later, Romario said it was a ‘show of respect’ from Baggio.

The decision by FIFA to schedule the final at 12.30pm in the middle of July, made with a European audience in mind, did little to help the spectacle. The 1994 World Cup final remains one of the worst in the competition’s history, with very little action amid exhausted players in energy-zapping heat killing any potential excitement. Baggio had one decent effort in the 90 minutes and another that — had he been fit — would’ve been expected to do better after a give-and-go with Massaro, yet the game mostly passed Baggio by, always on the fringes. His right hamstring visibly supported with heavy strapping.

“Maybe at the beginning of the game I couldn’t let go,” he wrote. “subconsciously I was worried about hurting myself, but after a while I got over that.” His withdrawn performance suggests otherwise.

Hungarian referee Sandor Puhl thankfully put everyone out of their misery and blew for penalties after 120 minutes of listless action. Baggio’s life would never be the same.

We all know what happened next. In a sport that can be as cruel as it can joyous, Baggio’s penalty miss was perhaps the greatest example of the former. If any player on the pitch didn’t deserve to miss a penalty — Romario aside — it was Italy’s No10.

“I knew Taffarel always dived so I decided to shoot for the middle, about halfway up, so he couldn’t get it with his feet,” Baggio explained. “It was an intelligent decision because Taffarel did go to his left, and he would never have got to the shot I planned.”

Aside from the fact that he brought Italy to the final, the cruel irony is that Baggio was, and remains, one of the best penalty takers in the history of Italian football, with a ratio of 85% from 127 competitive matches. Unjustly, he’ll always be remembered for one.

Baggio went for power and not precision, something he never did, and his penalty went over the bar. This brings us back to the beginning of this article and the picture: Taffarel on his knees in celebration; Baggio looking at the ground in sheer disbelief.

No matter that Franco Baresi and Massaro had already missed for Italy, and even if Baggio had scored, it was only delaying the inevitable Brazil victory, most chose to overlook those misses in favour of what has now become arguably the most famous missed penalty in the history of the game.

Baggio’s career suffered in the aftermath, playing for Italy only four times in the period post-USA ’94 and leading into France ’98. The already-strained relationship with Sacchi collapsed, who left him at home for Euro ’96. Minus the ponytail, Baggio won back the hearts of the Italian public at the 1998 World Cup, scoring two penalties and producing performances that earned him an ill-fated move to Inter.

That day in Pasadena still haunts Baggio. By his own admission he still dreams about it, wishes it could be erased from his career. Despite winning trophies with Juventus and Milan, scoring goals that can only be considered works of art and owning the hearts of Italians up and down the country, he cannot escape that sweltering July day 30 years ago.

And yet because of the miss, he’s loved even more for it. In the eyes of Italians, the miss made Baggio human, one of us, evidence that a man with god-like ability to do whatever he wanted with a football could still get things wrong. USA ’94 was supposed to be Baggio’s tournament and, after a difficult start, he came so close to fulfilling that destiny.

Future Italian players might’ve won more, but none leave the eyes misty like Baggio. The man who died standing in the Californian sun.

Watch out for DC Audio and Video content, like this one on Operazione Nostalgia

Related Articles

Related Articles

Football rivalries, world-class sport, surreal carnivals, and a tradition you won’t find anywhere else. Five events to catch in February.

In the latest edition of My Town, My Team, Napoli fan Alex told us why everybody should visit Naples at least once.

Sampdoria against Palermo at the Stadio Luigi Ferraris is just one of the standout matches to be shown live on Destination Calcio TV.