Murales di Diego: How Maradona Became a Global Symbol

By Emmet Gates

And there it was, all 45 metres of it – of him – in the dead of a humid Buenos Aires summer night. I was standing before the biggest mural of Diego Armando Maradona that’s ever been created on Avenue San Juan. Located in the Constitucion area of the capital, a street that in daytime is thronging with people coming and going is now deserted around 1am, leaving just Diego and I, the street lights below illuminating that classic Maradonian expression of defiance. Fist clenched, rallying the troops.

The sheer scale and scope of the mural is one of those times when articulating just isn’t enough; it simply has to be experienced. Covering an entire 14-storey building the mural, in case you haven’t seen it (picture below) depicts Maradona in the final of Italia ’90 against West Germany in Rome, with Argentina playing in their resplendent dark blue away shirt.

Created by muralist Martin Ron and his team of seven, the mural took 25 days of intensive work to finish in time for what would’ve been Maradona’s 62nd birthday. The image was chosen by Maradona’s two daughters and his ex-wife. Ron said: “I chose this photo because we know that Maradona was the best footballer in history and in this photo appears the Diego that all Argentines know – the warrior who fights against all adversity and shows his passion to win.”

Having stood in silence for what felt like an eternity before arguably the greatest footballer that’s ever lived, craning my neck upwards and gazing at its splendour, I went home. Venturing back a second time on my second-to-last night of a two-week holiday in Argentina, the mural lost none of its impact.

Yet this isn’t the only mural of Maradona in Buenos Aires. Like Naples, his face is everywhere. Nor is it even the only large-scale mural of him in the capital. Another giant Maradona painting was created by Maxi Bagnasco near Ezeiza airport, with the idea being people descending into the city from the air can catch a glimpse of one of the nation’s greatest sons. The mural, nearly as high and wide as the one in Avenue San Juan, shows Maradona sometime between 1987 and 1989 in the classic blue and white home shirt of Argentina, eyes focused on the opposition, no doubt planning their eventual defeat.

Throughout the capital, Maradona is omnipresent, especially in La Boca. Having been to see Boca Juniors twice, the area surrounding La Bombonera, in the heart of the poor-but-vibrant district that’s close to the port, depicts Maradona in all stages of his life: the young, fresh-faced Maradona that played for Boca in the early 1980s; Maradona after bamboozling the English at Mexico ’86 in the dark blue shirt found a day before in Mexico City; latter era Maradona with a Cuban cigar clenched between his teeth cheering on Boca from the stands; mid-00s and post-stomach surgery Maradona with a sleeveless Boca shirt showing off his Che Guevara tattoo. And in different styles, from tiled mosaics to painted mosaics, Buenos Aires isn’t short of creativity for Diego.

There is no footballer or athlete more-immortalised on walls and the side of buildings around the world than the man from a shanty town on the periphery of Buenos Aires. Aside from the Maradona-heavy territories of Buenos Aires and Naples, murals can be found in cities like Mexico City, Dublin, Lima, Beijing, Santiago, Montreal, La Paz, Barcelona, Limassol, Podgorica and even London where, despite some lingering bitterness over the Hand of God, a mural resides in Brick Lane.

Maradonaland

Going to Naples in 2024 is like peeking into Maradonaland. From the moment you arrive in the city, you’re greeted with images of that face everywhere. In fact, it would be more difficult to go around Naples and avoid Maradona.

Yet it wasn’t always this way. Having been to the city in the mid-2010s, the only mural of Maradona was the now world-famous one in Quartieri Spagnoli. Painted in 1990 by local artist Mario Filardi following the club’s second Scudetto in 1989/90. Filardi died in 2010 and the mural was reinvigorated six years later after it had been left to fade away for years, with the area once a stronghold of the Camorra and generally off limits to tourists and even many locals.

Since his death in November 2020, the mural and the square in which it resides has morphed into a pilgrimage for football fans the world over. The space where once vespas and small cars parked has given way to everything related to Maradona: from shirts to flowers to scarves and everything in between, the narrow, claustrophobic streets now rammed with visitors every day. When Napoli welcome away teams, some make it their mission to visit the mural as a sign of respect. A Maradona museum recently opened a stone’s throw away from the old car park, something unthinkable a decade ago.

“Maradona represented the redemption of this city,” remarked Roberto Saviano, the Naples-born journalist whose book ‘Gomorrah’ resulted in round-the-clock protection from the Italian state for the last 16 years.

“With him, Neapolitans had something they felt proud of, something they were respected for.

“You see, Maradona marked a change. He showed the Neapolitans that big teams, like real problems in life, can be beaten. Maradona taught Naples that you can win.” It was recently reported in the Corriere dello Sport that the mural was Italy’s most-visited tourist attraction in 2023 after the Colosseum, with over six million visitors.

Such is the number of Maradona murals around the world that the Instagram account — ‘maradonamurales’ — has over 1,300 posts showcasing tributes in various forms and surfaces. Run by Argentine journalist Nico Reyes for several years, Reyes was contacted by Maximo Randrup, a professor of journalism at the University of La Plata and a regular contributor to Argentine daily La Nacion, with the proposal of collaborating on a book dedicated to the murals after Randrup had written an article for Norwegian website Josimar on the same topic.

“When I wrote a piece about Maradona’s murals, I realised that the topic deserved more exploration,” Randrup tells Destination Calcio. “There are so many murals, all around the world. I thought that it was worth the effort of compiling them so that a good portion of the pieces dedicated to Diego were on a book for people to enjoy and at the same time to know where they are located. Every photo has its location.”

The book was eventually titled ‘Murales De D10S’ and contains some 128 pages of Maradona murals on five continents and dozens of countries, including some of the most unlikeliest places on earth.

Maradona the symbol

The adulation in Argentina and Naples is understandable, considering what Maradona means to both, but what is it that sees his face adorned on walls in countries and cities he likely never visited, let alone played in? The book contains murals in the likes of Iraq, New Zealand, Kenya and Lebanon, countries that couldn’t be more diverse and far-reaching.

Yet footballers, especially one with the global appeal of Maradona, need not have played in various countries to mean something. According to Randrup, the man from Villa Fiorito represents a symbol to many: “I think that Diego crossed the borders of Argentina and Naples and became a universal idol. Maradona belongs to everyone and I believe many people see him as a symbol of resistance.

“Besides what he did on the pitch, Diego stood up to power, and that made many see him as an idol beyond the football pitch,” he adds. For Reyes, people could relate to him because Maradona wasn’t merely a footballer. “Throughout his life, he went through different versions and chapters, which allows not only us Argentines but also a person in Ireland to say: ‘I want him on my wall, and I want to see him reflected there every day’.”

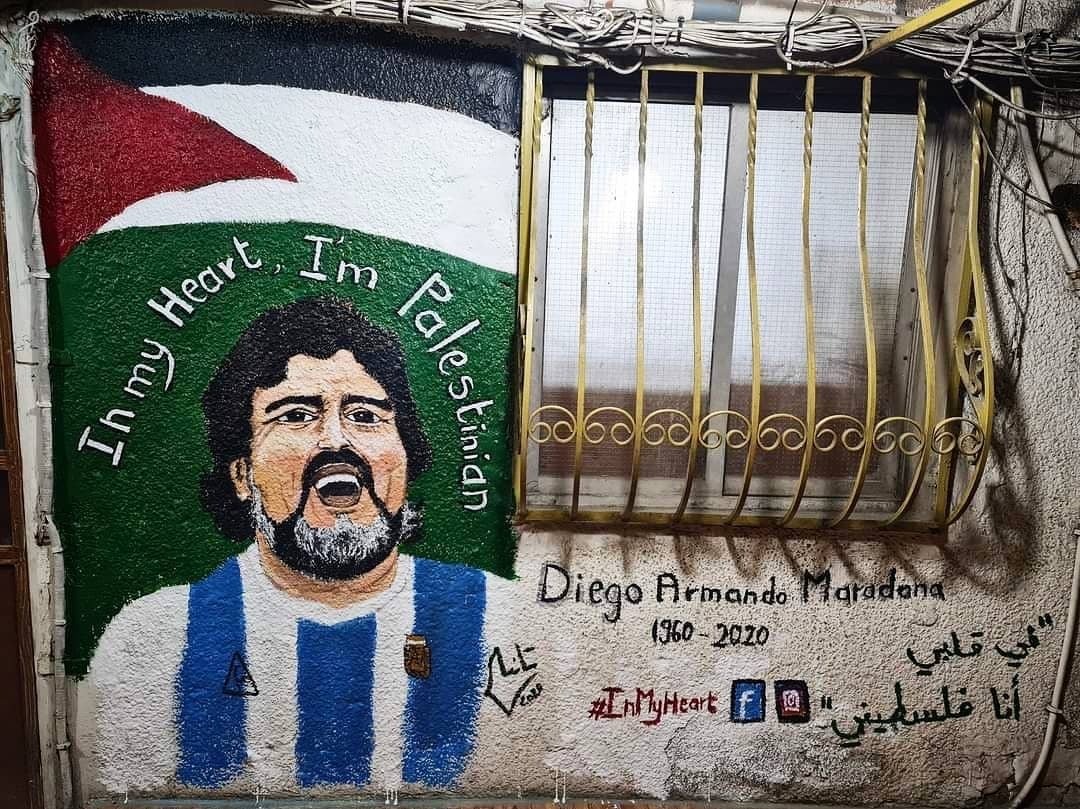

Case in point is a mural of Maradona in a Palestinian camp in north Lebanon that depicts not Maradona the player, but the man. Maradona, never shy to vent his political feelings during interviews and could count on Fidel Castro as a personal friend, admitted he stood by the Palestinian people in 2012 and met the president of Palestine, Mahmoud Abbas, in 2018. “He took a stand where, perhaps today, footballers fear giving an opinion,” says Reyes. “Well, he wasn’t like that. So, there’s a mural with Diego proclaiming himself as Palestinian, also linking himself to one of the important causes in the world regarding territory and social issues.”

Asking Randrup where the most ‘out-there’ mural to feature in the book is, he points to one in Syria where Aziz Asmar, a Syrian muralist, can be seen painting a fresh mural amid the crumbling ruins of a house in the northwestern city of Idlib after bombing from the Assad regime. Asmar painted the mural in the days following Maradona’s death in November 2020 and admitted to watching games of him in his youth.

When probed on their favourites, Reyes and Randrup point to different murals. For Reyes it’s emotional, as the one painted on a wall in the San Telmo area of Buenos Aires, depicting Maradona mid-run, head up and chest puffed-out during a game in Mexico ’86, was the first he saw after attending his wake at Casa Rosada. “That mural holds emotional significance for me,” he says. “There were already candles, flowers, and many things [at the mural] that truly made him seem like a deity, a person who was no longer among us.”

For Randrup, it’s one produced by Quique Spinetta in Berazategui, a city in the province of Buenos Aires. Spinetta’s depicts early 80’s-era Maradona with bushy hair, but in this instance Spinetta works the environment to his advantage: using an actual tree for the hair, with the low wall underneath hosting his face.

Argentina’s World Cup triumph in Qatar has firmly put the ‘Maradona or Lionel Messi’ debate in session for the rest of time, so will we eventually see as many Messi murals in due course? Reyes doesn’t believe so. “I don’t think even Messi, with everything he represents, will ever have as many murals worldwide,” he muses.

“Maybe because, as mentioned before, Diego had so many chapters in his life, where there’s a mural for a phrase, a mural for a political stance, a mural for representing Argentinians—not just as a footballer, but as a person.”

‘The most human of the gods’

One of Reyes’ proudest moments was having Maradona’s youngest daughter, Gianinna, involved with the book: “Having Gianinna write some words and seeing them [with Maradona’s other daughter, Dalma] get emotional when they saw it — all that makes me think that if he were still with us, he would have been very proud to have it in his hands.”

Despite the completion of the book, Reyes continues to post new Maradona murals on Instagram every day. “Murals come to me from all over the world,” he says. “I’m amazed by the places where, I don’t know how, they manage to connect with Diego.” Reyes admits the project was merely supposed to last a month, but has ‘snowballed’ and he continues to post not just as a tribute to Maradona, but to the artists across the globe who take the time to depict him.

With new murals popping up around the world seemingly every day, could a second book be on the cards? “Possibly,” laughs Reyes. “But we are very happy with the work we’ve done.”

The legendary Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano once declared Maradona to be the most “human of the gods”, and perhaps this gives us a clue to his continual ability to both provoke and inspire people across the world. Maradona’s life is relatable to all of us: a man who touched the sky, who represented the absolute pinnacle of the sport — or indeed any sport — in 1986, but who also plumbed the depths of addiction and the struggle with near-unparalleled levels of fame.

And for as long as people can relate to Maradona, the murals will continue. Reyes and Randrup might just be making a second book quicker than they imagined.

Related Articles

Related Articles

Football rivalries, world-class sport, surreal carnivals, and a tradition you won’t find anywhere else. Five events to catch in February.

In the latest edition of My Town, My Team, Napoli fan Alex told us why everybody should visit Naples at least once.

Sampdoria against Palermo at the Stadio Luigi Ferraris is just one of the standout matches to be shown live on Destination Calcio TV.