Monza’s Sale to BLV Marks the End of Silvio Berlusconi’s Great Sporting Empire

By Dan Cancian

Monza’s sale to US-based investment firm Beckett Layne Ventures (BLV) increases the American influence on Italian football and marks the end of one of the peninsula’s greatest sporting dynasties.

Relegated to Serie B at the end of last season, the Brianzoli join the ever-growing list of teams with US owners.

Both Milan clubs, Fiorentina, Parma, Pisa, Hellas Verona, Roma are under American control, as is a 55% stake in Atalanta.

Bologna are owned by Canadian millionaire Joey Saputo and in Serie B a US consortium is in charge of Spezia.

In a statement earlier this week, Monza confirmed 80% of the club’s shares will be transferred to BLV this summer, with the remainder to be processed next June.

The American investors have paid €45m (£38.8m) for the club, which includes €15m worth of debt, for their first foray into the world of football.

Founded and managed by Brandon Berger and Lauren Crampsie, BLV has so far invested north of $10bn (£7.3bn) in the media and entertainment sectors. While football in Monza has always lived in the shadow of the neighbouring Milanese giants, the city is synonymous with Formula 1.

Monza is home to the oldest purpose-built racing circuit in mainland Europe and the third-oldest in the world after Brooklands in England and Indianapolis in the US.

The track has hosted the Italian Grand Prix since the opening edition of the Formula 1 world championship in 1950 and recently signed a six-year extension to remain on the calendar at least until 2031.

Their arrival in Monza marks the exit from football of the family of the late Silvio Berlusconi, whose Fininvest holding company took control of the club in September 2018.

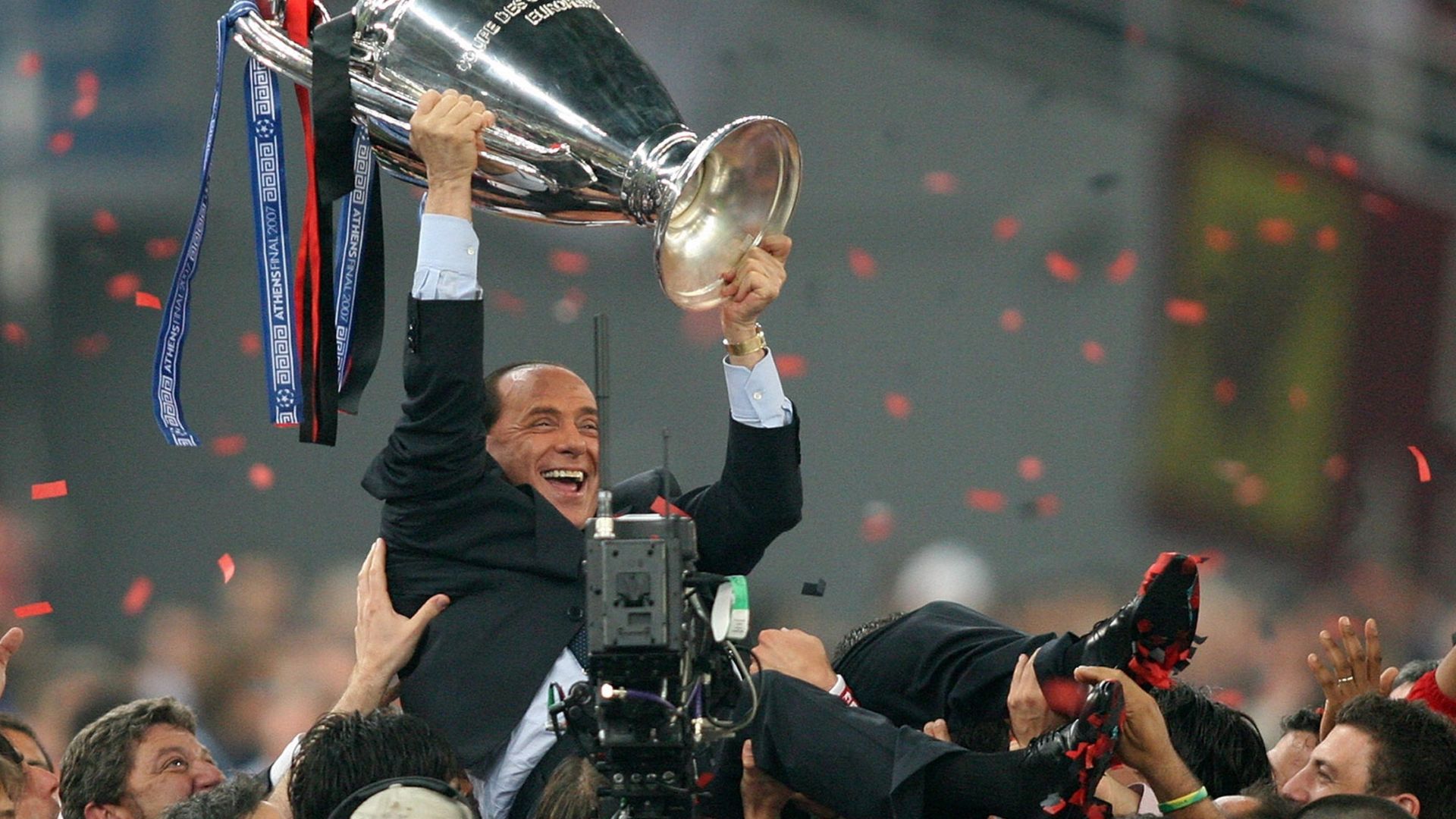

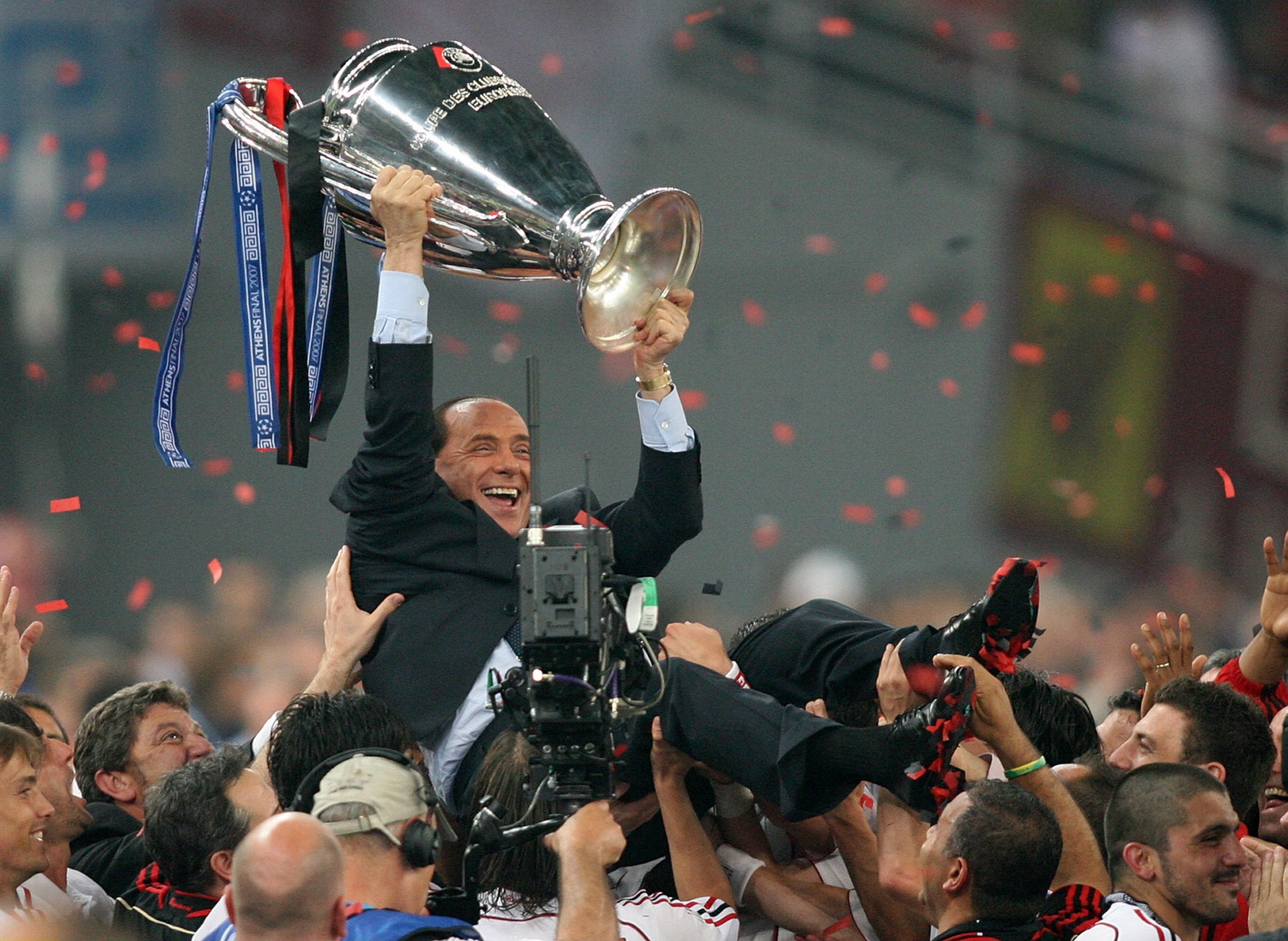

Berlusconi, a four-time Italian prime minister and media tycoon, won 29 major trophies during 31 years in charge of AC Milan.

Fininvest – whose name originated from the merger of the words “finance” and “investment” – was founded in 1975, 11 years before Berlusconi replaced Giussy Farina as Milan president.

One of Italy’s youngest and most successful entrepreneurs, Berlusconi had built his fortune on his private TV network, managing the hitherto impossible feat of ending RAI’s monopoly on Italian broadcasting.

If anything, the prospect of turning the Rossoneri around looked an even more arduous task.

Relegated to Serie B in 1980 because of their involvement in the Totonero match-fixing scandal, Milan were demoted to the second tier a second time two years later, this time simply owing to staggering ineptitude on the pitch.

By the time Berlusconi hired Fininvest executive Adriano Galliani to be Milan’s new CEO, Il Diavolo was seven years removed from their most recent Scudetto.

Berlusconi, of course, not only returned Milan to the role of domestic powerhouse, he transformed them into the greatest club side in the world of their era.

And perhaps any era, in fact.

Never one to be overly concerned by popular consensus, Berlusconi rolled the dice by appointing Arrigo Sacchi in 1987, plucking the former shoe salesman from the relative obscurity of Serie B.

The rest is history. Sacchi won the Scudetto in his first season in charge. Two European Cups followed over the next two campaigns, along with two European Supercups and two Intercontinental Cups.

When an exhausted Sacchi stepped aside in the summer of 1991, Fabio Capello picked up the baton and arguably made Milan even better.

Like his predecessor, Capello’s arrival was met by doubts, with then-Udinese manager Franco Scoglio famously declaring his appointment “an insult to fellow managers”.

Skepticism proved to be spectacularly misplaced.

The Rossoneri won the Scudetto four times in five seasons under Capello, lifting the Champions League and European Supercup in 1994 along the way and scooping up three Supercoppa Italianas.

A decade later, Carlo Ancelotti authored Berlusconi’s third and final great era.

One of Sacchi’s most trusted lieutenants, Ancelotti lifted the Champions League twice, along with six other major trophies, chief among them the Scudetto in 2004.

But Berlusconi’s plans extended far beyond football.

Three years after taking control of Milan, Fininvest bought Milano Baseball 1946, Amatori Milano Rugby, Hockey Club Devils Milano and Volley Gonzaga Milano.

Berlusconi only missed out on adding Olimpia Milano, the city’s basketball team, due to strong opposition from their owners, the Gabetti family.

A man whose ambition was only outsized by his ego, Berlusconi wanted to mirror Barcelona and Real Madrid’s approach by building an empire across different sports as Polisportiva Mediolanum.

The latter part of the name was a nod to one of Italy’s biggest financial companies, in which Fininvest held a 50% stake.

All teams were given identical kits: white or red, featuring the Fininvest logo, the Mediolanum wordmark, and the team name vertically down the centre.

This served the dual purpose of being a powerful brand identifier and an effective propaganda tool.

In each of the new sports he entered, Berlusconi operated with the same agility and whirlwind energy he brought into football.

He overturned market rules by acquiring the best talent available or retaining them to the tune of exorbitant wages.

If Milan were led by the Dutch triumvirate of Ruud Gullit, Marco van Basten and Frank Rijkaard, Volley Gonzaga Milano could count on Andrea Zorzi and Andrea Lucchetta, world champions with Italy in 1990.

Amatori Milano, meanwhile, featured Australian rugby legend David Campese along with Italian rugby great Diego Dominguez, one of only eight players to score over 1,000 points in Test rugby.

If handing Milan’s reins to Sacchi was a risk, Berlusconi travelled in a completely different direction in volley, appointing Doug Beal, who had led the US to Olympic glory on home soil at the Los Angeles games in 1984.

But while trophies flowed in football, success was harder to come by in other disciplines.

Amatori Milan won two league titles, while Hockey Club Devils won the Scudetto three times and lifted the Alpenliga – a now defunct competition contested between teams from Italy, Austria and Slovenia – once.

Baseball delivered two Cup Winners’ Cup and two Coppa Italia titles, while Volley Gonzaga won two Club World Cups and one Cup Winners’ Cup.

Worse still, with the exception of Volley Gonzaga, which drew average crowds of 7,000 fans, the Polisportiva teams never established themselves into the city’s sporting fabric as much as Milan had done.

By 1994, political ambitions took precedence over sport for Berlusconi, spelling the end of his Polisportiva dreams.

Ironically, of course, he borrowed from the sporting lexicon as he announced his arrival on the political scene in Italy, by famously declaring he “would take to the pitch”.

“I’m very sorry, but I can no longer intervene in certain decisions,” he said shortly after being elected prime minister as he announced Fininvest’s withdrawals.

By the time Berlusconi stepped away, Amatori and Gonzaga had finished the previous season in second place, while Hockey Club Devils had just won the Scudetto.

Amatori would win two more titles in 1995 and 1996 before finishing second the following season, but folded in 2011.

Volley Gonzaga never reached the same heights again as they drowned in financial problems and were eventually demoted to Serie B, while Hockey Devils relocated to the Aosta Valley in 1996.

Milano Baseball, meanwhile, have bounced around the lower tiers of the Italian pyramid for the past three decades but returned to Serie A last year.

Milan, of course, were the major exception to the rule, remaining successful until Berlusconi stepped down in 2017. A year later, he took control of Monza, investing a total of €285m in the club and taking Galliani with him.

The Brianzoli returned to the Serie B in 2020 after a 19-year absence and clinched their first-ever promotion to Serie A in 2022, a year before Berlusconi’s death.

BLV’s arrival in Monza marks a new dawn for the club, but the end of an era for Italian sports.

Related Articles

Related Articles

Football rivalries, world-class sport, surreal carnivals, and a tradition you won’t find anywhere else. Five events to catch in February.

In the latest edition of My Town, My Team, Napoli fan Alex told us why everybody should visit Naples at least once.

Sampdoria against Palermo at the Stadio Luigi Ferraris is just one of the standout matches to be shown live on Destination Calcio TV.