Golazzo: Fabrizio Ravanelli, Parma vs. Juventus, 1995

By Emmet Gates

The art of the diving header is slowly being phased out of football.

Once a staple of the game, in the latter half of the 20th century one could witness at least one exquisite diving header per-season in top flights across the world, likely even more.

Yet as we reach the middle of the 2020s, the diving header is all-but extinct, a relic of a bygone era.

The emphasis on passing and cutting the ball back when getting to the opposition’s byline means we no longer live in a world where the winger crosses the ball into the box. In the Premier League, for example, crosses declined from 17 in open play per-90 minutes at the start of the 2010s to just under 13 a decade later.

Serie A, in contrast, had the most open play crosses per-90 minutes at the start of the same decade from Europe’s top five leagues with 18, but plummeted to around 13 by the end of the 2020-21 campaign.

Crosses weren’t seen within the game as being effective in producing goals, and the Pep Guardiola effect, where possession and passing was now king, had taken hold of Europe.

With every side now ostensibly playing the same way, crossing is becoming ever more diminished and thus the chances of headers — let alone diving headers — being scored reduce to scarcity status.

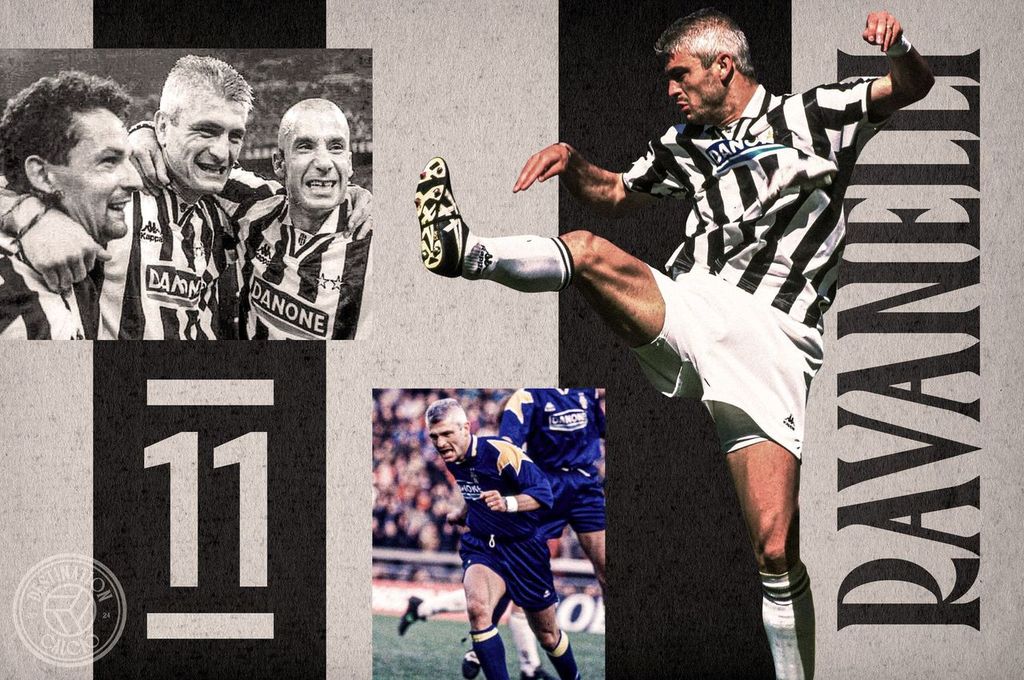

With that in mind, one of the best diving headers of the 1990s belonged to Fabrizio Ravanelli. La Penna Bianca (The White Feather) scored an outrageous goal against Parma in January 1995, exactly three decades ago to the day, in what was the best season of his career.

As the opening day of the 1994-95 season dawned, Ravanelli was in his third year at Juventus. Yet the general consensus on the forward was that he was a good squad player and nothing more. Ravanelli had faced a wave of competition upon his arrival from Reggiana in the summer of 1992.

With the likes of Roberto Baggio, Gianluca Vialli, Andy Moller, Pierluigi Casiraghi and Paolo Di Canio all vying for two places, to say competition was fierce would be an understatement. Yet Ravanelli still posted good numbers despite limited playing time: nine goals in all competitions in 1992-93 was followed by 12 the following season.

Ravanelli was perhaps third or fourth fiddle in those campaigns, a supporting actor at best. He was soon to get a starring role under new coach Marcello Lippi.

The cigar-smoking manager arrived in the summer of 1994 and adamant of making change. It’d been eight years since Juve last won the Scudetto. Eight too many for their liking.

After several flat performances at the beginning of the season, including an embarassing 2-0 defeat to Foggia, Lippi devised a 4-3-3 system to make up for the loss of Dino Baggio, sold to Parma the prior summer.

Baggio had been capable of running from midfield and weighing in with vital goals, but with him gone and Lippi’s current midfielders incapable of scoring the number of goals the Italy international could provide, Lippi added in an extra attacker in order to make up the shortfall.

Vialli was at the point of the three, with Ravanelli on the right and Roberto Baggio either on the left of floating wherever he liked.

The effects were immediate: Juve won their next six games on the bounce, including a massive win over reigning champions AC Milan at Stadio Delle Alpi, with the winner coming from a rare Baggio header.

A draw with Genoa dampened spirits before going into the Christmas break. Yet Juve were only a point behind league-leaders Parma. Juve’s next game? Away to the Gialloblu in early January.

Fuelled by the goals of Gianfranco Zola, Marco Branca, Baggio and the odd sprinkling of stardust from Faustino Asprilla, Parma produced a terrific first half of the season and would go on to challenge Juve for every competition that season.

Serie A has never quite seen anything like it before or since, two sides battling for domestic and European supremacy in the one season. The two teams would play each other six times in 1994-95 across three different competitions.

But this was the first meeting, at the Stadio Ennio Tardini on a frosty Emilia-Romagna afternoon.

Ravanelli and Vialli were joined in attack by Alessandro Del Piero, who’d replaced the injured Baggio since the end of November with such gusto that Juve would take the gamble to offload the world’s best player at the end of the season.

Parma boss Nevio Scala had built his success at the Gialloblu on a 5-3-2 system, a rarity at the time in the Italian game. Scala’s 5-3-2 would morph into a 3-5-2 when in possession.

Zola was used at the tip of the midfield three to support and create for Asprilla and Branca, with the less-famous Baggio making them surging runs into the box from midfield that Lippi lost out on.

Baggio had already scored four times in Serie A for his new club, and would go on to produce a career-best season.

The opening 45 minutes at a sold-out Tardini saw several missed chances from both sides. For the home side, Asprilla missed what was essentially an open goal when the ball fell for him no more than three yards out after Juve failed to clear their lines from a Zola corner. The Colombian somehow blasted his shot over the bar.

For Juve, playing in their dashing blue away shirt that would be a staple for the club for the rest of the decade, Ravanelli and Vialli both wasted chances, with the former’s arguably the easier of the pair.

But 12 minutes into the second half the deadlock was broken by the home side.

Asprilla picked up the ball from Zola near the centre circle and pushed forward, Baggio ran on the outside of the Colombian and timed his run behind Juve’s back line to perfection. Asprilla slid a perfectly weighted through ball into his path, and Baggio marched into the Juve box to rifle a shot past Angelo Peruzzi to make it 1-0. It wouldn’t be the last time the lesser-known Baggio punished his old club that season.

Yet Juve weren’t behind for long. Paulo Sousa had been a recent summer signing from Sporting Lisbon and the Portuguese midfielder was an underrated part of the Bianconeri’s eventual domestic double.

Sousa found himself down near the left-hand touchline with the ball at his feet. He swung in a cross that went over everyone’s head, including substitute Parma goalkeeper Giovanni Galli — who’d come on for the injured Luca Bucci — and nestled into the corner.

It was an accidental goal, yet Lippi and Juve didn’t care, for the game was now level.

Nine minutes later came Ravanelli’s masterpiece.

Moreno Torricelli went on a foray into the Parma half before sliding the ball to his right and into the feet of Vialli, who’d broke behind the Parma line down the right-hand side.

Vialli let the ball continue to roll, looked up and hit a hard cross towards Ravanelli, who was in the centre of the field just outside the penalty box.

Ravanelli made a darting run into the box in an attempt to shake off Fernando Couto and Nestor Sensini — not the easiest of tasks — before throwing himself at Vialli’s cross.

Ravanelli, now resembling a Boeing 747, met the ball with the left-side of his head, directing his diving header into the bottom corner of Galli’s goal, giving the former Napoli and AC Milan stopper absolutely no chance.

It was a pure Roy of the Rovers goal: a heroic diving header — while fielding off the challenge of two grizzled defenders — against a major opponent in a big-time game that turned the course of the match. According to Ravanelli his nickname, La Penna Bianca, originated here, due to comparisons with a similar goal scored by Roberto Bettega.

It was arguably the greatest goal of Ravanelli’s career, and demonstrated just how much he’d grown under Lippi and was no longer a supporting actor at Juve, but an integral part of the Juventus show that was about to dominate the rest of the decade.

He added a second just four minutes later, when Vialli was foolishly hauled down by Lorenzo Minotti inside the area. It was a silly decision by the usually reliable Minotti, with Vialli going nowhere.

Juve’s No11 promptly fired the ball down the middle of Galli’s goal to send Juve home and dry.

Ravanelli would go on to score 30 goals in all competitions, the best season of his career by a long way, and dedicated the goal to a child from Perugia who was suffering from leukaemia.

“He was released from the hospital just before Christmas and asked me for a special goal. I hope I’ve made his day,” said Ravanelli in a nice touch.

The win put Juve back on top of the table, and they never looked back. Despite losing six games in the second half of the season, they’d go on to win the league by some 10 points ahead of Lazio and Parma.

They’d lost more games in one season than previous champions Milan had in the prior three Scudetto-winning campaigns combined, with the Rossoneri machine finally spluttering.

The crowning moment of Juve’s long-awaited journey back to the summit of the Italian game came on May 21 against Parma at the Stadio Delle Alpi. Baggio, now back from injury, produced a monumental display, providing three assists in a 4-0 win.

Yet Juve and Parma weren’t finished jiving. The pair met in the then-two-legged Coppa Italia final, which Juve won 3-0 on aggregate, and the then-two-legged Uefa Cup final, which Parma won 2-1 on aggregate.

Parma’s win in Europe, courtesy of two Dino Baggio strikes in either leg, denied Lippi a historic treble in his first season in Turin.

For Ravanelli, his performances in the 1994/95 season saw him nominated for the Ballon d’Or that year, finishing 12th alongside Ajax’s Frank Rijkaard.

Despite winning the Champions League a year later — and scoring in the final to boot — this was the best season of Ravanelli’s career. A campaign when it could be argued he was the best striker in Serie A.

Related Articles

Related Articles

Football rivalries, world-class sport, surreal carnivals, and a tradition you won’t find anywhere else. Five events to catch in February.

In the latest edition of My Town, My Team, Napoli fan Alex told us why everybody should visit Naples at least once.

Sampdoria against Palermo at the Stadio Luigi Ferraris is just one of the standout matches to be shown live on Destination Calcio TV.