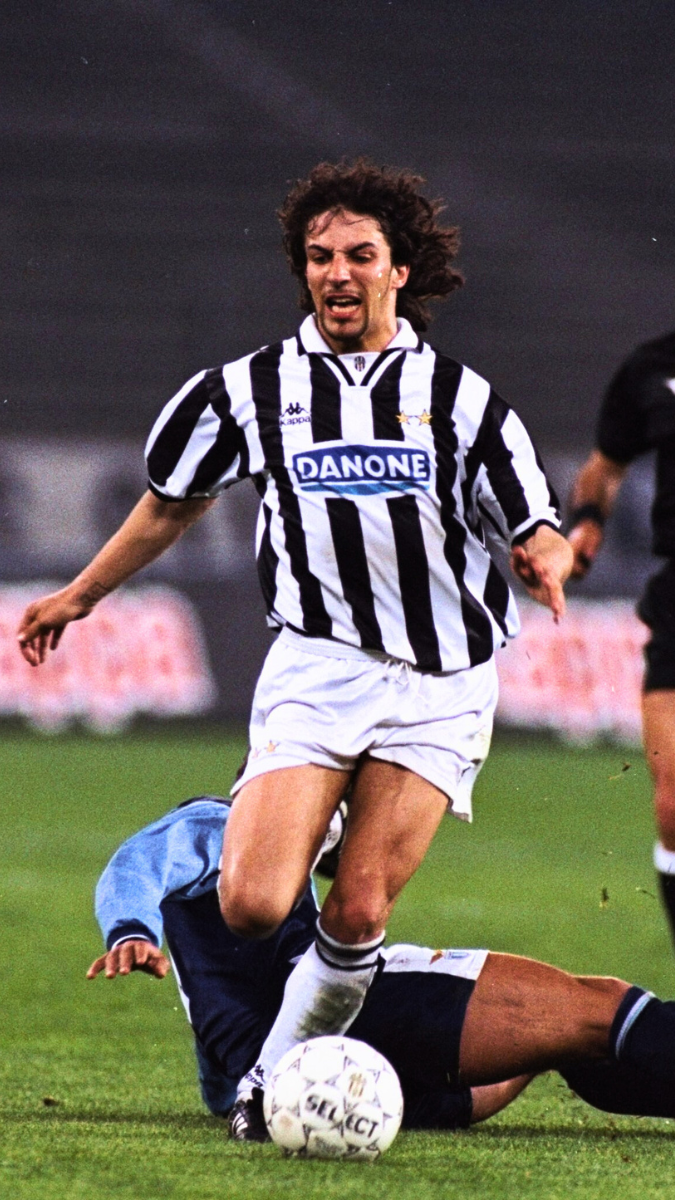

Golazzo: Alessandro Del Piero, Lazio vs Juventus, 1994

By Emmet Gates

Bernardino di Betto was a renaissance-era painter born in Perugia in the middle of the 15th century.

Famous for his works in the Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome and Siena Cathedral, Di Betto is better known to the world as Pinturicchio (The Little Painter).

Pinturicchio, who died in 1513, has always been closely associated with the great Italian painter Raphael, the pair graduating from the same renaissance school in Perugia and later working together.

Fast forward nearly 500 years and by December 1994 the new Pinturicchio was making a name for himself, but with feet rather than hands.

A bushy-haired kid called Alessandro Del Piero was on the cusp of great things. He was having his breakout season at Juventus, and his world would never be the same again.

Del Piero had signed for Juve in the summer of 1993 from Padova, and played sporadically under Giovanni Trapattoni in his first season.

Usually filling in for Roberto Baggio whenever the “divine one” was injured, he made 14 appearances in all competitions for the Bianconeri in 1993-94, scoring five goals in Serie A, including a hat-trick against Parma that signalled this was a potential superstar in the making.

Despite still being in the era of the three foreigners rule, Serie A clubs still inhibited a distrust of youth. For a 19-year-old to be handed starts for Italy’s biggest club was evidence in the tremendous faith from the boy born in Congeliano.

Del Piero wasn’t born that far from Baggio, with Congeliano and Caldogno just over an hour’s drive within Veneto, and soon their careers would be intertwined for years.

By the beginning of the 1994-95 season, Juve hadn’t won a Scudetto for eight years, and Marcello Lippi was brought in to replace Trapattoni and handed a single objective: to knock AC Milan off their mighty perch.

Lippi had vowed to make Juve less ‘Baggio-dependent’ by arguing that Juventus had been easy to nullify over the past four years, simply by doubling up on the world’s best player.

Yet Lippi simply couldn’t drop the reigning Ballon d’Or holder. The Tuscan was smart and not stupid, he needed an opening. He got it in an away game against Padova in late November.

Baggio had scored a trademark free-kick in the first half, but was forced to come off in the second half due to a knee injury. The prognosis wasn’t good; he’d be out of action until the early spring.

Lippi had tinkered his formation early on after a shock 2-0 defeat to Foggia. Going from a flat 4-4-2 to a more dynamic 4-3-3, with Baggio allowed to drift wherever he pleased, this saw a major upturn in Juve’s results in the autumn and early winter.

Now with Baggio out, Del Piero was entrusted with the iconic No10 shirt and utilised on the left-hand side of Lippi’s 4-3-3, with Gianluca Vialli through the centre and Fabrizio Ravanelli on the right. Lippi was using inverted wingers two decades before it became en vogue across Europe.

The first match post-Baggio was the classic 3-2 comeback against Fiorentina at the Stadio Delle Alpi. Del Piero produced arguably his most memorable goal, the winner in the last minute to steal a victory for The Old Lady after being 2-0 down by half-time.

The next week saw the Bianconeri travel to the capital to face Zdenek Zeman’s Lazio, and another classic was in the making.

A rain-soaked Stadio Olimpico played host to one of the best games of the 1994-95 campaign, with both teams going full throttle from the off. Watching back some 30 years later, the pace was truly unrelenting for the age.

Both Angelo Peruzzi and Luca Marchegiani were called into action multiple times before Roberto Rambaudi scored for Lazio in the 20th minute following great work from Beppe Signori down the left-hand side of the Juve area.

Seven minutes before half-time Del Piero scored his first of the match, sliding in ahead of Marchegiani after controlling Alessandro Orlando’s beautiful in-swinging cross before prodding home the loose ball.

Giancarlo Marocchi made it 2-1 to Juve early in the second half, with the midfielder lunging to meet Antonio Conte’s cross from the right, his effort smashing off the crossbar en route to goal.

Then Del Piero made it three.

The criminally underrated Paulo Sousa fizzed a low ball into his feet deep in the Lazio half. With his back to goal, Del Piero pivoted to his right and shifted past Paolo Negro and ran down the left-hand channel.

Negro was in hot pursuit as Del Piero was seemingly running into nowhere. Now faced with the pair of Negro and Argentine defender Jose Chamot on the periphery of the Lazio area, it appeared Del Piero was boxed in. Surely he would be dispossessed by two grizzled and experienced Lazio defenders.

The No10 had other ideas.

Del Piero again began to run straight before cutting in between the tiny gap left by Negro and Chamot with his left foot, wriggling past them. Now entering the Lazio penalty area from the left-hand side, Del Piero — failing even once to look up — bent the ball into the opposite corner of Marchegiani’s goal, giving the Azzurri stopper absolutely no chance.

The term ‘Zona Del Piero’ wouldn’t enter the football lexicon until the autumn of 1995, when he scored carbon copies of this goal time and again in the Champions League against Rangers, Borussia Dortmund and Steaua Bucharest, but the Lazio goal was the original, the first of its kind.

Juve would make later make it 4-1 thanks to future Blackburn legend Corrado Grabbi, who started his career at Juve but would be sold to Modena two years later.

Lazio pulled two late goals back through Pierluigi Casiraghi and Diego Fuser, but Juve would win the game 4-3.

Del Piero had scored three goals in a week, two of them brilliant, and it was within those seven days Lippi realised he no longer needed Baggio in Turin. He’d found his new superstar.

Del Piero could, at that stage, offer more dynamism, defensive diligence and tactical flexibility than Baggio. A more amenable character, Del Piero was favoured by Italian coaches for the rest of their careers because Del Piero was simply willing to do the kind of work Baggio loathed.

For Lippi, tactical supremacy trumped genius, and while there was no bad blood between the pair at this point (that would come later at Inter), Lippi didn’t stand in the way of his departure.

Legendary Juve patron Gianni Agnelli had christened Baggio with the nickname ‘Raphael’ due to his ability to produce masterpieces on a semi-regular basis. In the summer of 1995 during Juve’s annual game at Villar Perosa, Baggio was now gone, sold to AC Milan, and Agnelli was asked to give Del Piero a similar nickname.

Agnelli mused it over for a few seconds and then compared Del Piero to Pinturicchio. The nickname stuck.

Pinturicchio’s work is often mistaken for Raphael’s, who was the more celebrated Umbrian artist and considered one of the finest painters of the renaissance period. This mirrors the Baggio-Del Piero dichotomy, with Baggio cemented as the greatest Italian attacker of all-time and Del Piero in the conversation but further down the pecking order, often overlooked by Italy’s most-beloved and innately talented footballer.

Yet for a brief period in time Pinturicchio stepped out of Raphael’s shadow, and proved he could produce masterpieces of his own.

Related Articles

Related Articles

Football rivalries, world-class sport, surreal carnivals, and a tradition you won’t find anywhere else. Five events to catch in February.

In the latest edition of My Town, My Team, Napoli fan Alex told us why everybody should visit Naples at least once.

Sampdoria against Palermo at the Stadio Luigi Ferraris is just one of the standout matches to be shown live on Destination Calcio TV.