Football in Genoa: The Most Secular of Faiths

By Dan Cancian

“Football is the most secular of faiths,” the late Genoese songwriter Fabrizio De Andre once reflected.

“It’s the need to align ourselves with a party, which is symbolised by images, by a colour, but which claims to be supported by a tradition and a culture different from those of others.

“Being a fan is born from a somewhat childish, but nevertheless human, need to identify with a group.”

A proud Genoese and an even prouder Genoa fan, De Andre brought his city’s rich tapestry to life through his music.

Football is ubiquitous in Genoa and is as deeply embroidered in the city’s fabric as Genoa’s proud maritime and textile traditions and its culinary delicacies.

Walk through the carruggi – the old town’s narrow and winding streets that were once lined by warehouses close to the port – and you’ll stumble upon murals dedicated to either Sampdoria or Genoa.

Stop at one of the hundreds of bakeries selling freshly-made focaccia – a staple of Genoese cuisine – and chances are it will have a flag hung behind the counter.

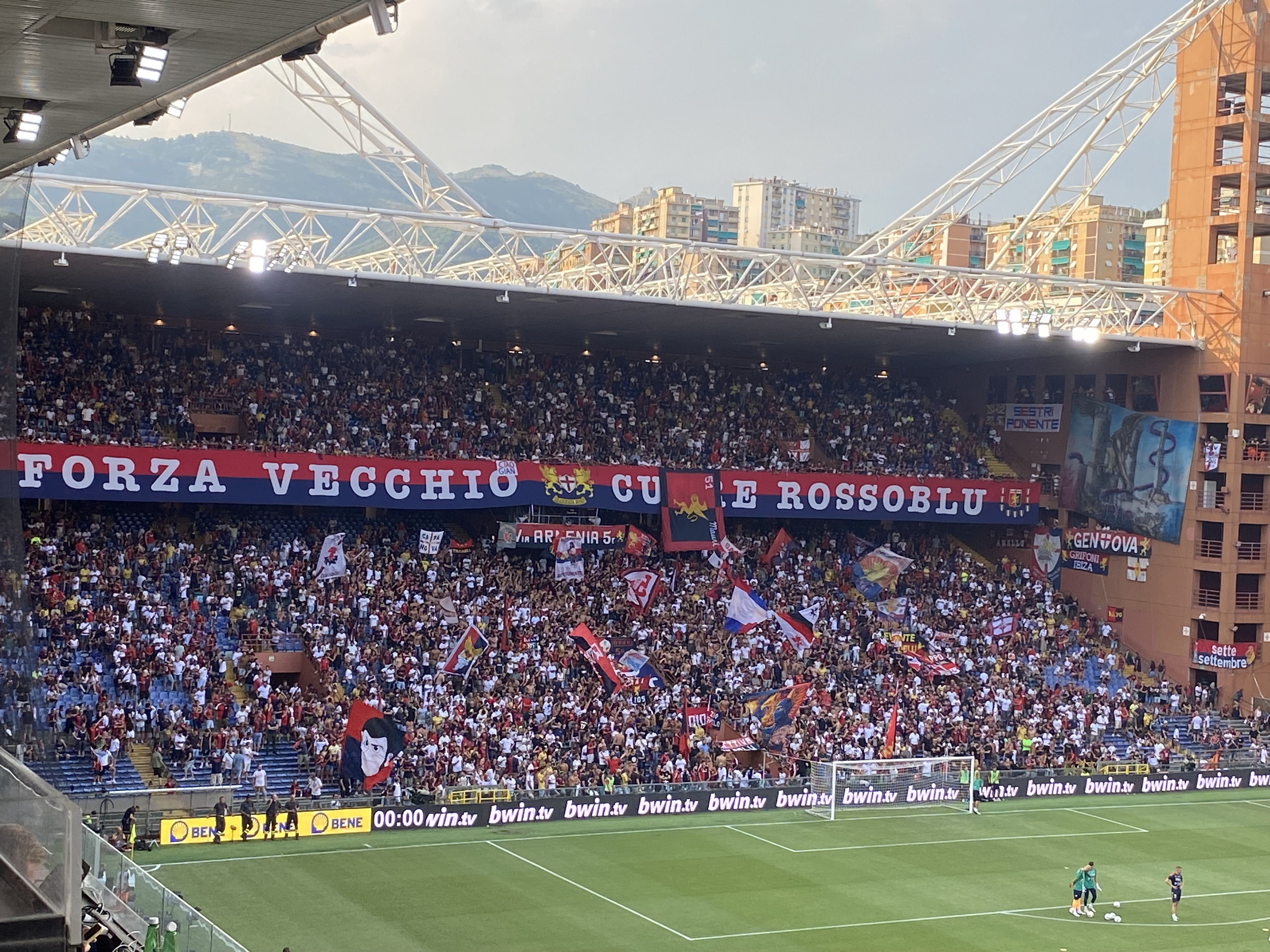

In the Stadio Luigi Ferraris, Genoa’s love affair with football has its perfect theatre.

Like some corners of the city itself, at first glance the ground looks slightly dated, hardly a surprise considering it last underwent a major revamp ahead of the 1990 World Cup.

But in an era of identikit and increasingly sterile stadiums, Marassi – as it is known after the working class neighbourhood it is situated in – remains one of the most picturesque grounds on the Peninsula.

A derby like no others

Crucially, it also provides by far one of the most electric atmospheres in the country when Sampdoria and Genoa square off in the Derby della Lanterna – which owes its name to the Lighthouse Tower, Genoa’s ancient landmark and the main lighthouse for the city’s port.

Marcello Lippi, who spent a decade with the Blucerchiati as a player, described it as “the most special in Italy.” High praise coming from a man who managed in the Turin and Milan derbies.

Significantly, rather than the curve – curved stands behind the goal – that characterise most Italian grounds, the Ferraris is famous for its two Gradinate – flights of steps behind each goal resembling the English-style ends.

Expect Marassi to be at its raucous best when Genoa and Sampdoria square off for the 108th time on Wednesday in the Coppa Italia, their first meeting since the Rossoblu‘s return to Serie A in 2023 coincided with the Blucerchiati’s relegation.

This may be the first iteration of the Derby della Lanterna in over two years, but distance hasn’t made the heart grow fonder between the two sets of fans.

“We have no cousins,” proclaimed a giant tifo flag in the Gradinata Sud ahead of Sampdoria’s clash with Bari last month.

It may seem an odd message, until you realise that in Italy teams that share the same city are referred to as cousins.

A day later, Genoa were welcomed onto the pitch by an ear-splittingly loud rendition of Sara’ Perche’ Ti Amo – It Must Be Because I Love You. A number 1 hit in 1981 by Italian pop group Ricchi e Poveri, in Genoa fans’ version romance has been replaced by something altogether more blunt.

“It must be because I love you. Being a Genoa fan, that’s what we’re all about,” they sang.

“I’ve hated the Doriani since the day I was born.”

Indoctrination in Genoa begins at an early age. Like in Manchester, Liverpool, Buenos Aires or Milan, you are either red or blue. Fence-sitters need not apply.

It is no surprise to see the flame of local rivalry burn so bright. After all, the Genoese are notoriously proud people and refer to their city as La Superba – The Superb One.

Trailblazers on and off the pitch

Founded in 1893, Genoa are Italy’s oldest club, something Rossoblu fans take fierce pride in and a stick often used to metaphorically beat their city rivals, who are 53 years younger.

Sampdoria, as Marassi’s stadium announcer never fails to mention, may have “the most beautiful shirt in world football”, but did not see the light until the merger of Sampierdarenese and Andrea Doria in 1946.

Yet the Blucerchiati have been pioneers in their own right, albeit off the pitch, as the Ultra Tito Cucchiaroni group claim to have introduced the word “ultra” into calcio’s lexicon.

Formed in 1969, the group were one of the trailblazers in the world of Italian organised fan groups and take their name from Ernesto “Tito” Cucchiaroni, who earned instant cult hero status after scoring twice on his Derby della Lanterna debut.

Both clubs’ relative lack of success of late has also narrowed the focus and made getting one over their local rivals more important than it ever was. Campanilismo, as the Italians refer to bragging rights, is the very essence of the fixture.

Sampdoria’s Coppa Italia triumph in 1994 was the club’s sixth major trophy in a decade and hitherto the last. The most recent of Genoa’s nine Serie A titles, meanwhile, dates back to 1924.

Yet support remains unwavering.

The Rossoblu have sold just over 28,000 season tickets this summer, while the 19,000 sold by the Blucerchiati are by far the most of any Serie B club.

Considering the Ferraris’ capacity is just north of 33,000, those numbers tell their own story. It is no wonder that Genoa have retired the No.12 shirt in honour of their fans.

But while the Derby della Lanterna is the Genoese football’s raison d’etre, Marassi is a sight to behold week in, week out.

Take the fixtures Destination Calcio attended last month for example. The atmosphere for Sampdoria vs Bari belied the fact this was a meeting between two teams languishing at the bottom of the Serie B table.

Tifo flags swaying rhythmically as the smoke of flares quickly filled the hot summer afternoon air, Marassi was a sea of blue, black, red and white as Samp fans paid a poignant tribute to the late Sven-Göran Eriksson.

In his first game in charge of Sampdoria Andrea Sottil was suitably moved.

“I want to commend the fans, they were incredible to watch. It was really moving,” the 50-year-old, who replaced Andrea Pirlo in the dugout, said.

“They sang, cheered on the team, and gave them a standing ovation. This is the kind of connection we need to build between the team and the supporters.”

The following day, meanwhile, a spine-tingling rendition of You’ll Never Walk Alone rang around the Ferraris ahead of the match against Verona.

Marassi’s great English paradox

Watching flags being waved and scarves held aloft reinforced the feeling that this is an English stadium in all but its address.

And yet, therein lies Marassi’s great paradox.

The atmosphere at the Ferraris does conjure memories of English grounds, but it’s the kind of atmosphere which is conspicuously absent from Premier League stadiums.

In that respect, the words of late Genoa manager Franco Scoglio feel relevant.

“Remember you are Genoa’s real custodians,” Scoglio, who managed the Rossoblu in three different spells, once said.

“Just like your fathers were before you and their grandfathers before them.

“You have history, you have culture, you have to represent Genoese pride.”

That process is made easier when an adult season ticket on the Gradinata Sud – which hosts Sampdoria’s ultras – costs €205 (£172), and a season ticket on the Gradinata Nord – home to Genoa’s hardcore fans – will set you back €270 (£227).

To put the figures into context, the cheapest season ticket in the Championship comes in at £250 at Coventry, while the most affordable in the Premier League will set you back £345 at West Ham.

No wonder then, that the crowds at Marassi before both games look decidedly younger than in England, where the average age of matchgoing supporters has been ticking higher for years.

If the prices make it affordable for young supporters to attend, Italy’s relaxed attitude to standing in football grounds does the rest, with fans in both Gradinate on their feet long before kick-off and throughout the 90 minutes.

The end result is a cauldron of colour and noise, where fans are as part of the spectacle as the football itself.

This is not to say that everything is perfect in Italian football, for it patently is not. Racism remains a huge issue that is proving difficult to eradicate, while several ultras groups across the country wield a dangerously high level of power on the clubs.

At the same time, over the past two decades, a series of law decrees aimed at curbing hooliganism have been dismissed as draconian attempts to systematically dismantle the very essence of organised support and limit fans’ freedom of non-violent expression.

But the two aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. While it is undoubtedly true certain elements of Italian football remain hostage to the ultras, it is also true that plenty of organised fan groups make calcio the spectacle it is.

Walking through the streets of Marassi on Saturday and Sunday amid a cacophony of noise and colours it was impossible to dispel the notion that, as De Andre put it, being a fan is born from the need to identify with a group.

If football really is the most secular of faiths, few cities can match Genoa for the fervour of its beliefs.

Related Articles

Related Articles

Football rivalries, world-class sport, surreal carnivals, and a tradition you won’t find anywhere else. Five events to catch in February.

In the latest edition of My Town, My Team, Napoli fan Alex told us why everybody should visit Naples at least once.

Sampdoria against Palermo at the Stadio Luigi Ferraris is just one of the standout matches to be shown live on Destination Calcio TV.